Life is full of phenomena that seem impossible to explain away by facts. Why is it that even though miles traveled are equal, the car ride to your vacation destination always feels longer than the car ride home? Why is it that my husband can bounce out of bed at 6 AM for an early tee time, but most other days need a snooze alarm and two cups of coffee to greet the day? Why is it that stocks keep going up against a backdrop of horrible economic data? While I will never be able to answer the first two questions satisfactorily, we can look to facts to at least partially explain the last.

The stats are grim. US Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the value of economic activity in a country, contracted sharply in Q1 (-5%) and is expected to show an even greater decline in Q2. The unemployment rate sits around 14%. There have been over 100 large bankruptcies filed so far in 2020. Prices on oil futures plunged and drifted into negative territory at one point. Global cases of coronavirus are 7.2 million and counting, and related deaths are 400,000 and climbing. Against this backdrop, as of June 10th, the S&P 500 is up 43% from its March low, global stocks have regained more than $20 trillion in value, and the Nasdaq rose 11% in 2020. The numbers are confounding and show a disconnect between the market and the economy. What gives?

It is important to keep in mind that although related, the market is not the economy. You can liken it to the image captured below.

The mom and the toddler are both headed in the same direction (the park?), but one moves faster and in a more circuitous route. They eventually get to the park, but the trip there was not the same experience for the mom (exhausting) and the toddler (exhilarating). Markets and the economy are headed in the same direction, but the journey there is not necessarily the same for each.

The economy is a snapshot of today’s conditions and what the most recent numbers tell us about what we have just experienced. Markets are forward-looking as they aggregate and price in what business conditions will be in the future. The markets are looking at what might impact a company’s cash flows and, in turn, the stock’s value. If these numbers turn out to be more favorable than anticipated, the markets will react positively; we saw this when the Dow was up 3% in one day when May employment numbers came in much higher than expected. In the past few weeks, we have seen some upside to economic expectations, such as better job numbers and positive guidance from the Federal Reserve, which has helped boost markets.

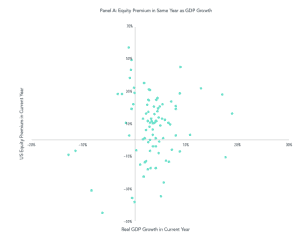

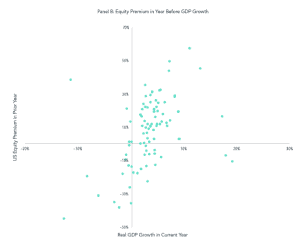

To support the premise that markets are forward-looking, we can look at historical data. Below are two graphs that plot US GDP and the equity premium (the excess return that investing in stock provides over risk-free security such as a 1 month Treasury Bill) from 1930-2019. The first graph looking at the equity premium in the same year as GDP growth shows no strong correlation, suggesting there is no strong relationship between GDP and current market returns. The second graph plots GDP growth against the prior year’s equity premium. This time, we see a relationship that suggests that market prices react in advance of economic developments.

While many factors may contribute to the current disconnect between markets and the economy in the time of Covid-19 (i.e., actions by the Federal Reserve, shorts covering their bets, investor sentiment, and experience after experiencing the 2008 crash and subsequent bull market), it is helpful to look to the data for historical perspective. Bottom line, you can’t use the words markets and economy interchangeably. Robert Schiller, Nobel Laureate economist and author of Narrative Economics, puts it this way, “The stock market is just that- it’s a market for shares of companies. It does have some relation to the economy, but it’s not as strong as people think. It depends on the story, and the story’s always changing.”

While many factors may contribute to the current disconnect between markets and the economy in the time of Covid-19 (i.e., actions by the Federal Reserve, shorts covering their bets, investor sentiment, and experience after experiencing the 2008 crash and subsequent bull market), it is helpful to look to the data for historical perspective. Bottom line, you can’t use the words markets and economy interchangeably. Robert Schiller, Nobel Laureate economist and author of Narrative Economics, puts it this way, “The stock market is just that- it’s a market for shares of companies. It does have some relation to the economy, but it’s not as strong as people think. It depends on the story, and the story’s always changing.”